1950 Bathurst Street, Toronto, ON, M5P 3K9

(416) 789-3291

[email protected]

Emergency Funeral Contact

Cell: 416-565-7561

Every once in a while, we archivists come across something that strikes a chord within us because of the current state of the Jewish world. Today, sadly, we are witnessing a resurgence of antisemitism in a raw and blatant form.

In 1935, Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath (our rabbi from 1929 to 1943) visited Germany and Palestine. Returning to North America, he landed in New York and was interviewed by a journalist. The report of that interview, published in The Reform Advocate, a Chicago Jewish periodical, and elsewhere, is our first record of Rabbi Eisendrath’s observations. Rabbi Eisendrath had visited Germany in 1933 and found the Jewish population “completely terrorized,” but now circumstances had become even worse.

“I saw evidences,” [Rabbi Eisendrath said,] “of new violence in the shattered name plates of Jews in front of several buildings. Then too, I saw the lorries filled with Brown Shirts on Kurfurstendam stopping in front of the various cafes, shouting ‘Jude Verrecke,’ and heard inflammatory speeches denouncing Jews who have the temerity to visit the cafes. On the whole, Jews do not frequent these cafes. These lorries had posters on them with slogans condemning both Catholics and Jews.”

“The passerby cannot, of course, glimpse the horror of the actual daily existence of the German Jews—the constant fear, the communication by whispers behind bolted doors and barricaded windows . To get below the surface, I spoke to a number of Jews and non-Jews. The situation, as everyone put it, is most heartbreaking and utterly hopeless. I spoke with a Jew from rural Germany who had come to Berlin. Not a customer had been permitted to enter his store for three weeks. Storm-troopers stood guard outside his doors to prevent anyone from entering. A recent development is not merely to refuse to buy from Jews, but to refuse to sell anything to them as well—not even the provisions needed for sustenance. Life is absolutely impossible for them in the small towns. In 1933 they were able to seek refuge in Berlin, but today their oppressors drive them from Berlin.”

In Palestine, Rabbi Eisendrath said, he had spoken to hundreds of young Germans who were exuberant and joyful over their escape from Germany. Magnificent work, he said, has been done in providing habitation for these refugees and some of the finest buildings he saw in most of the colonies were built with relief funds. The German Jewish youth, he added, are unanimous in their desire to rebuild their lives in Palestine, and in addition to the young people, erstwhile professional men and business men have been so completely affected by what has happened, that they want nothing more than to make a complete break from everything that is German—land, language, culture, and to reshape their lives in Palestine.

“I would like to add my personal testimony,” he said, “to the imperative necessity for continued relief in Germany. The people are starving. The only possible escape for the youth is by training them for admission to some other country. We must provide funds to give them the chance to escape.”

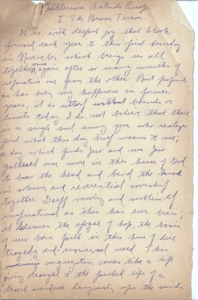

Once back in Toronto, Rabbi Eisendrath made it his task to tell audiences, Jewish and non-Jewish, of the horrors being endured by Jews in Germany and the urgent need to assist Jewish refugees in Palestine. A page from a manuscript of one of his addresses accompanies this article.

An early and acute observer of the situation in Germany, Rabbi Eisendrath’s experiences led him to reevaluate his opinions on pacifism and Zionism; something we will write more about in future articles in these pages.

Michael Cole and Howard Roger

By Susan Cohen, member, Holy Blossom Archives Committee

Photo by Paul Hellen

One of the most emotional symbols of Israel at Holy Blossom Temple is at the same time one of the smallest and most hidden.

Climb to the very top of the second floor above the Alice and Bernard Herman Chapel and you will see five small windows completing the stained glass series that makes the synagogue so distinctive. The artist Peter Haworth began the design in 1965 but it took eight years for the complete group to be developed and dedicated. These windows reflect the theme of ‘place‘: our hope for a universal world (a small rose window symbolizing the United Nations), our love of Canada, and two windows portraying our previous synagogues on Richmond St. and Bond St.

The Israel window is the fifth window on the south wall; it was one of the last to be dedicated (in 1972). Look closely and you will see a map of Israel and in the upper left in tiny form the country’s official state seal, along with the message in Hebrew: “Zot Ha-aretz l’Zarachah Etnennah”. (This is the land … I will give unto thy seed. Deuteronomy 34:4.)

Israel’s official seal is a menorah with two olive branches. The menorah is actually the same one depicted in the Arch of Titus in the Roman Forum. That arch celebrated Rome’s victory in the Jewish-Roman war 66 – 74 C.E. One of the carved reliefs depicts the menorah, part of the spoils of war, carried aloft by the Jewish captives. When the seal was being designed, some objected to using that specific menorah which they felt was a symbol of the Temple’s destruction, but the creators of the seal were motivated by a different vision, seeing it as representative of Israel’s rebirth.

As small as this window is, it reflects Holy Blossom’s long-standing interest in Israel. One of our earliest presidents, Alfred Benjamin, was a president of the first Zionist Society organized in Toronto in 1898. Temple’s influential Rabbi Solomon Jacobs appeared at a Zionist meeting in 1908 and declared his sympathy with the movement. The “firebrand” Rabbi Abraham Feinberg advocated for Israeli statehood and our Director of Education, Heinz Warschauer, gave our students textbooks with biographies of Theodore Herzl and Joseph Trumpeldor to read. Holy Blossom has held the land of Israel close to its heart for well over a century.

(The Archives Committee receives inquiries regularly. We invite you to contact us about this or other areas of interest at: [email protected] We are always interested in learning and sharing more about our remarkable history. We also encourage you to examine the archival displays in the Schwartz-Reisman Atrium.)

By Judy Winberg, Member, Holy Blossom Temple Archives Committee

During the Yom Kippur Yizkor services, we will read:

“…We remember too, the men and women who but yesterday were part of our sacred congregation and our community. … … Their memories will forever be a blessing.”

And so, our teachings guided us as we tried to unravel a mystery that found its way to our Archives committee almost one year ago. Neighbours of the Temple’s first cemetery on Pape Avenue were excavating their backyard when they found a headstone, believed to come from a grave there.

The time-weathered stone, about 15 inches square and weighing 50 lbs., had faded Hebrew lettering. The stone itself was intact but far from its original location. The headstone was delivered to the Temple, and the effort to solve the mystery began.

To whom did this headstone belong? When did the burial take place? How did it come to be buried in a backyard on Austin Avenue? And what, according to halacha (Jewish law and tradition) should we do now that it was in our possession?

Efforts to learn more about the original location of the grave and who may have been buried there were in vain. The stone was so eroded that, despite exacting best archival techniques, the wording could not be deciphered. We reached out to the past Chair of the Temple’s Cemetery Committee and the Ontario Jewish Archives; we consulted our clergy and sought legal counsel regarding the Ontario Cemeteries Act and Bereavement Authority of Ontario. Sadly, there was little to guide us. While our tradition teaches that we are to honour and respect the dead, the law is silent on any protocol for returning a headstone to its original location.

Still, during our investigation, we unearthed (pun intended) a treasure – written records of the burials as Pape Avenue from a long-lost map marking the names and locations of 200+ graves. Many graves were assigned to children and many of those were located around the cemetery’s perimeter. It may be that the headstone belonged to a child; short life expectancy was not uncommon in the late 19th century.

We felt that the most appropriate action was to return the headstone to its original resting place.

This summer, members of the Archives Committee conducted a historical walking tour of the Pape Avenue Cemetery for congregants and a few curious members of the local Leslieville community. The tour ended at a location that divides the cemetery from the neighbour’s backyard. We carefully returned the headstone there and placed it horizontally on the ground. We conducted a short ceremony for the unknown Temple member and, in our tradition of visiting a grave site, small stones were placed on its surface.

While the return of the headstone brought some closure the mystery surrounding it remains unsolved.

The Pape Avenue Cemetery, sometimes called Jews’ Cemetery was established in 1849 by a small group of unaffiliated Toronto Jews. Ownership was transferred to the fledgling Holy Blossom congregation in 1858 and burials took place from then until the early 1940’s. Holy Blossom Temple owns the land and maintains the cemetery to this day.

An interesting article about this cemetery, “Jewish Life in Stone” appeared in 2008: https://www.thestar.com/life/jewish-history-in-stone/article_b2f7ad9c-8763-5975-a3b9-42b1772f2c37.html

The Archives Committee receives inquiries regularly. We invite you to contact us about this or other areas of interest at: [email protected] We are always interested in learning and sharing more about our remarkable history. We also encourage you to examine the archival displays in the Schwartz/Reisman Atrium.

By Howard Roger

Our Archives Committee recently received a question from a librarian at the Bora Laskin Law Library at the University of Toronto. She had been contacted by an archivist in the US (from the NAACP) inquiring about Thurgood Marshall’s speech for the Holy Blossom Temple Brotherhood Forum on February 28, 1955. Did we have any information? We did indeed, and our search uncovered a fascinating coincidence.

Thurgood Marshall was a distinguished civil rights lawyer and legal counsel for the NAACP. In 1967 he became an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, the first Black to be appointed to that position. But he was, in 1955, already well-known for his successful argument before the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education. That case established the rule that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. It was a watershed moment in American legal history, overturning the separate-but-equal doctrine previously upheld by the Supreme Court in 1896.

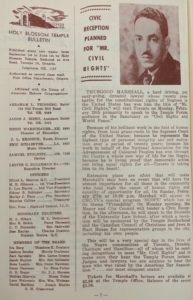

Thurgood Marshall spoke at Holy Blossom Temple on the evening of Monday, February 28, 1955. The title of his speech was “Civil Rights and World Peace.” A page from the Holy Blossom Temple Bulletin of February 23, 1955 (see photo) describes not only his upcoming appearance at Holy Blossom, but also other events which he would be attending while in Toronto, including an appearance Sunday night on CBC television, a Civic Reception Monday morning with the Mayor (Nathan Phillips, a member of Holy Blossom) and the City Council, an address in the afternoon to the students of the University of Toronto Law School, and a reception at Hart House hosted by Holy Blossom Temple Brotherhood and the Canadian Council of Christians and Jews.

The article about Thurgood Marshall appears on the right-hand side of the Bulletin page. If you look at the bottom left-hand side of the same page you will see the name of Bora Laskin, who was, in 1955, a professor at the U of T law school and a member of the Board of Holy Blossom Temple. Bora Laskin had, in 1950, assisted the Canadian Jewish Congress in the case of Noble et al v. Wolf, a case before the Supreme Court of Canada which ruled that a restrictive covenant, prohibiting the ownership or occupancy of land “by any person of the Jewish, Hebrew, Semitic, Negro or coloured race or blood,” was void and unenforceable. In 1970 Bora Laskin was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada, the first Jew to be appointed to that court, and he became Chief Justice in 1973.

The article about Thurgood Marshall appears on the right-hand side of the Bulletin page. If you look at the bottom left-hand side of the same page you will see the name of Bora Laskin, who was, in 1955, a professor at the U of T law school and a member of the Board of Holy Blossom Temple. Bora Laskin had, in 1950, assisted the Canadian Jewish Congress in the case of Noble et al v. Wolf, a case before the Supreme Court of Canada which ruled that a restrictive covenant, prohibiting the ownership or occupancy of land “by any person of the Jewish, Hebrew, Semitic, Negro or coloured race or blood,” was void and unenforceable. In 1970 Bora Laskin was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada, the first Jew to be appointed to that court, and he became Chief Justice in 1973.

We could not find any information on whether Bora Laskin was involved in making any of the arrangements for Thurgood Marshall’s visit to Toronto or attended any of the events. Still, our research has shown how two future Supreme Court justices came together (at least on paper), and reminded us how the history of Holy Blossom and the history of civil rights in Canada and the United States intersect.

You may wish to visit the Archives Committee displays at the far end of our atrium as well as the Living Museum display by the elevator.

If you have any items of archival interest to contribute to the Holy Blossom archives, we would love to hear from you. Please e-mail us at [email protected].

By Judy Winberg, Archives Committee

Holy Blossom Temple’s archives collection houses treasures which are historically significant not just to the congregation, but to the Jewish community in Toronto and elsewhere. Some were gifted by congregants, and many were endowed by the families of the original owners. It’s been an honour to work with the archives and to be one of the custodians of our congregation’s rich history.

The collection is varied. Historic papers such as legal documents, contracts, original deeds and maps, drawings, and photographs testify to the early days in the life of the congregation. More recent holdings include official minutes of the Temple’s Boards of Directors, the Temple Foundation and committees. Printed programs and tribute books chart significant events at Temple while photographs, manuscripts, prayer books and hymnals, as well as works of art document our cultural and spiritual life as a congregation and are proudly and carefully maintained by the Archives Committee.

As you enter the main sanctuary through the Schwartz/Reisman Atrium take a moment to examine an important artifact from 1857 in a specially designed showcase. It’s the original Yad, the silver engraved pointer used to guide the reading of the Torah; it was received with the first Sefer Torah (Torah Scroll), donated to the “holy congregation Pirchei Kodesh (Holy Blossom) as a gift in perpetuity from the benefactor Elyakum, son of Isaac of the family Asher (and) his wife the lady Rachel”. (This translation was provided by the late Rabbi Dow Marmur z”l.)

The original Offering Book from 1876 recorded the weekly donations. Entries were made with a shoelace (no writing instruments on Shabbat!). It is preserved and on display in the historical Timeline showcase located along the north window wall of the Schwartz/Reisman Atrium.

In 1962 The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Holy Blossom Temple as part of a ‘Brotherhood Forum’ The program and follow-up letter of thanks signed by King can both be viewed in the Timeline showcase.

The parochet, or fabric curtain used to line the inside of the ark protecting the Torah scrolls (due to be re-installed in the anteroom of the Max E. Enkin Boardroom in the Lawrence Bloomberg Leadership Centre) is an interesting artifact because of the name on it – Sons of Israel. This name appears in our Minute Books as the name of the congregation four times in the early months of our existence in 1856. The name then disappears. We are not sure where the parochet was used (perhaps in our first location above Coombes Drug Store on Richmond Street). Decades later Executive Director, Mel Olsberg, found it among items returned to us from St. George’s Congregation which moved into our Bond Street location after the move to 1950 Bathurst Street.

These are just four examples of some of the archival objects that are in our safekeeping. Watch this space for more and if you think you may be housing some treasures in your homes and want to talk to us, please reach out to [email protected].

By: Sheila Smolkin

Who is this distinguished gentleman now looking at us from the wall in the Bloomberg Jewish Leadership Centre, just outside the Max Enkin Board Room? He is Edmund Scheuer (1847-1943) generally regarded as the father of Canadian Reform Judaism.

Scheuer moved to Hamilton, Ontario from Paris, France in 1871 where he became very involved in Anshe Sholom Congregation. Under his influence, Anshe Sholom became the first Reform Congregation in Canada in 1882. He had a dream in this new land; Jew and Christian, Synagogue and Church would work shoulder to shoulder for the ideals which both religions held in common, “The fatherhood of God who has created us all, and the brotherhood of all men.”

Scheuer moved to Toronto in 1886 where he established his business as a jeweller. He immediately joined Holy Blossom and was elected to the Board. He saw Jewish education as a privilege. He took charge of the synagogue’s school where he served as superintendent for several years, he wrote a number of young people’s textbooks, organized and taught a Confirmation class for girls, aged 13, which culminated in 1899, and he organized and financed the Zionist Free School for Girls run by 16 volunteer teachers from Holy Blossom.

Scheuer was dedicated to the Jewish community in many other ways as well. He founded the first Jewish Benevolent Society in Toronto and was the first president of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies.

During the 57 years that he was a member of Holy Blossom, Edmund served in almost every capacity in the synagogue. For his lifelong service, he was appointed Honourary President in 1934.

In 1920, influenced by the thinking of Scheuer, Holy Blossom took the first step to affiliate with the North American Reform Movement when it hired Barnett Brickner, ordained at the Reform theological school, Hebrew Union College, as its rabbi.

In 1943, at the age of 95, Edmund Scheuer was killed when hit by a streetcar on Yonge Street. As the historian, Michael Brown has written, Edmund Scheuer remained to the end of his life both an advocate of modernization and acculturation in Jewish life and a dedicated and proud Jew.

You may wish to visit the Archives Committee displays at the far end of the atrium as well as the Living Museum display by the elevator.

If you have any items of archival interest to contribute to the Holy Blossom archives, we would love to hear from you. Please e-mail us at [email protected].

From the Archives: Choirs, Cantors and Organs

By Susan Cohen

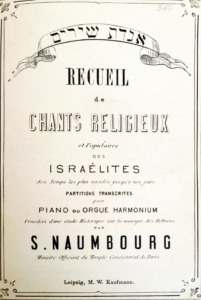

Collection of Religious and Popular Israelite Songs, with historical essay by composer Samuel Naumbourg; published 1874, found in Holy Blossom Music Archives

You can explore Holy Blossom’s archives through many lenses such as people, events, liturgy, or social action. Michael Cole and I have been reviewing musical archives prior to sending Cantor Emeritus Benjamin Maissner’s musical material to libraries in Israel and Germany.

It took 70 years to firmly establish the role of cantor at our synagogue. Our first ‘cantor’ (in 1879), Joseph Glueck may have been the first musically trained chazzan in Toronto, but he was also a teacher, baal koray, shochet, mohel and dues collector. No wonder he only lasted 3 years.

As the synagogue grew, the leadership looked for more distinguished clergy. Reverend Herman Phillips, a well-regarded and trained cantor from Europe, joined us next. Blessed with a rich baritone, he fulfilled the roles of teacher and spiritual leader as well as cantor. But music became a bone of contention between the orthodox and reformist wings of the synagogue. Feelings reached such a pitch in 1890 that dissident congregants dumped the synagogue’s portable organ outside and the board demanded its return. The use of the organ made Cantor Phillips resign, and a rabbi was hired that year who was not averse to the instrument.

Four years later the synagogue created a separate cantor’s position, filled by Cantor Sol Solomon. He came from Paris, the Rue de Nazareth synagogue, famed as the musical home of Samuel Naumbourg whose compositions we still sing today. Solomon likely brought Naumbourg’s choral and organ works to sing here; we have found some music books of that era in the archives. Entirely in keeping with Cantor Solomon’s background, our new synagogue on Bond St. (1897) made room for a permanent pipe organ and choir loft. Emma Yoemans took on the role of organist.

Cantor Solomon’s position was never entirely secure and he left in 1901. In letters we have in our archives, he told Holy Blossom President Alfred Benjamin that the synagogue had not treated him well nor was he appropriately compensated. There was even some dispute about whether he had properly taken music with him. Jewish newspapers of the time said that Holy Blossom could not afford both a cantor and a rabbi.

From 1901 until 1943 the synagogue employed no cantor at all, a not-unusual feature of Reform synagogues of the time. When our Bathurst St. building opened in 1938, there was space for a choir and organ, but none for a cantor, not even a cantor’s lectern. Still, the choir had many talented professionals in it, and some took on chazzan-like roles including Sam Stolnitz. He had been taught cantorial skills by his father and was a gifted singer formally trained at the Toronto Conservatory. In 1949 Rabbi Abraham Feinberg told the board that Stolnitz would share the “chancel” with him at services. We have been served by exceptional cantors ever since.

You may wish to visit the Archives Committee displays at the far end of the Temple Atrium honouring Rabbi Marmur z”l and The Pioneering Women of Holy Blossom, as well as the Living Museum in the Atrium by the elevator.

If you have any items of archival interest to contribute to the Holy Blossom archives, we would love to hear from you. Please email us at [email protected].

1950 Bathurst Street, Toronto, ON, M5P 3K9

(416) 789-3291

[email protected]

Emergency Funeral Contact

Cell: 416-565-7561